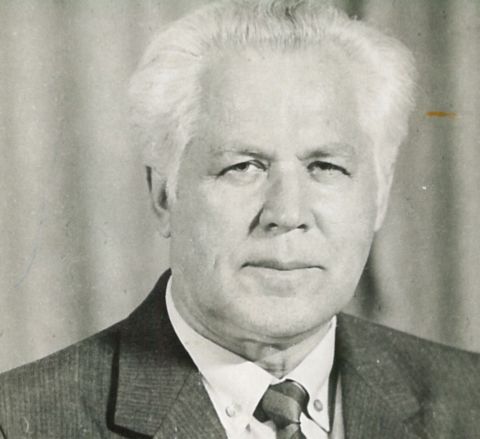

Eduard Gabrin was born on November 6, 1925 in Chelyabinsk. He graduated from the Moscow Institute of Finance and Economics.

His working biography begins in the fuel injection equipment workshop of Kirov Plant (Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant). From here he volunteered to serve in the army in 1942. At the age of 17 he took the oath of allegiance.

He served in the assault aviation corps in command of Georgy Baydukov. The young communist participated in the combat operations of the corps in the High Command reserve, acted as a Komsomol leader of an aviation regiment, and actively worked for the army front-line newspapers.

He celebrated the Victory Day in the Baltic states, where his regiment was located.

Here are the recollections of the veteran: "The life in the city switching to warfooting. Hospitals were being deployed in schools; and in the park on the Square of the Fallen, near the White barracks, a big mobilization centre was organized. All our carefree days of youth were cut short. I remember well a grandiose demonstration by the city working classes under the slogan "Hurl all effort into defeating the enemy!". July 1941 through autumn 1942, I worked as a lathe operator in the fuel injection equipment workshop of Kirov Plant (Chelyabinsk). From here, once I turned 17, I went into the army as a volunteer. Together with a group of my comrades we were sent to a military school. And only in summer of 1943 I found myself on the front, and only for a short period of time: I had to return to the military school after two months of training in one of the combat aviation regiments.

Our unit was based on the same aerodrome as the French Fighter Squadron "Normandie", which was transformed into a regiment. The French pilots, full of optimism and belief in the victory, were exceptionally cheerful people. Despite the language barrier, we could understand each other quite well. The very same aerodrome (called "Khatenki") was a base for the famous Night Bomber Regiment under the command of the celebrated pilot Bershanskaya. The preparation of the Orlov-Kursk operation was underway.

I graduated from the military school as an aviation ordnanceman with the second speciality of a "radio-operator gunner".

Also in 1943, I for the foist time experienced the bombing by the enemy. Though it seemed to me not that effective, so to say, back then. I was surprised to find out that bombs were dropped closely-grouped, and you feel like you watch this from the side. But when they are dropped quarter-section, you probably cease to be a mere observer… You become frightened. These things also happened. Bombing is a horrible thing!

Over the whole war-time period (and I'm talking about "my war-time" now), I did not happen to meet a fascist soldier head-on, not even once, except for meeting war prisoners. That was the specific feature of aviation, as the aerodromes were located 5-15 kilometres off the front line.

During the war we happened to be based on approximately thirty aerodromes in the action zones of the Western Front, the 1st and 2nd Belorussian Fronts, and the 3rd Ukrainian Front. Those are a great many points on the military maps, but as a rule, they are located away from settlements.

It is impossible to forget our commanders, especially those of the war-time period. As a Komsomol worker, I participated in two meetings with the corps commander, General G.F. Baydukov. And back when I had been studying, multiple times I observed the work of General A.V. Belyakov. Both of them were members of the famous Chkalov's crew team. I remember well the commanders of the regiment, squadrons, units, and separate crews. Meetings with the army commander General K.A. Vershinin (later, the chief marshal of the aviation) still stick in my memory. I met marshal K.K. Rokossovsky twice.

I served on the front for a little over a year. As a member of an assault aviation crew a participated in five combat missions. The most dreadful thing was to watch how my comrades died over the goal, when there was already nothing anyone could do to help them. And it was also very difficult to wait for the return of your comrades from combat missions. You already knew that there were losses, but you kept believing and hoping for a miracle, sort of. There were so many losses! Probably that was the main reason why people did not show off or boast about their medals. In any case, it was the way in the units I served at, even years and years after the war ended.

It was very difficult physically as well. The winter conditions were especially hard for the aviation maintenance personnel when they had to replace three worn-out air engines overnight. Daily routines in aviation units was at a high level, just like the procurement was.

I celebrated the Victory Day on my way from the front team back to our aerodrome. It was an indescribable joy mixed with heavy heart for the losses, for those how did not live to see this glorious day. I couldn't even believe that the war ended, that there would be no gun volleys, roar of dive planes, or bombing anymore, and that the number of orphans would stop growing…. I couldn't believe that a new peaceful life began."

After demobilization, Eduard Gabrin worked at the Department of Industrial Economics in the Chelyabinsk Polytechnic Institute (CPI).

He was awarded the Badge of Honour Order, Medals for Bravery, for Combat Service, for the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945, and more.